Last Sunday, my partner Sabrina and I embarked on our journey from elevated, compressed Washington Heights to the spaciousness of Cortelyou, Brooklyn. And as I walked, I saw many gardens. As we looked for the church, Sabrina remarked: it’s probably a house...where I see a house and read All Souls Bethlehem. And is that not what it is supposed to be….a home for those who are seeking. From the back of the worship space, I could see a homely staircase descend while people of different colors, ages, and genders entered and moved around.

Like the early church, we sang and we read scripture. And then something sacred began to emerge between all of us. Words began to rise, stories of disease and healing, murder and triumph. We sang and we greeted one another in one of the most non-awkward passing of peace. And then we raised the stories of a day that changed New York forever, that left tears on the eyes and lump in the throat for many in the room.

This July, looking over the Gri Gri lagoon in Rio San Juan, I managed to link to the Wi-Fi of our outdoor bar and a read news that forever changed my view of my homeland. I was visiting my partner’s relatives in the Dominican Republic, and as the power blinked in and out, the words of my uncle brought a weight I could not push away: I slowly read the news of the Russian “anti-terrorism” law that imposed an oppressive clutch of restrictions on the religious freedom, and really freedom of conscience, of my Russian people. “Religious activity” outside “designated places” is now illegal.

This is an incredibly weighty matter for me. I was nurtured by the courage of those who, because of their religion, suffered Soviet persecution in Stalin’s labor camps or discrimination and brutality in their communities: my great-grandfather and grandfather spent ten and five years, respectively, in Stalin’s gulags; my father and mother challenged school and military authorities, facing discrimination and physical brutality. In fact, I witnessed this authoritarianism when my father’s visa back to the US was delayed for months in 2004.

That night, I poured tears for the people of my land and all peoples because we could not share this planet without the unjust structures of power and control. I poured tears for Latin Americans othered in their own lands, Haitians deported both from the United States and the Dominican Republic in a larger crushing of difference, of blackness. These were human issues, these were issues that emerged right here at All Souls Bethlehem Church.

The brutality, the fragmentation of relationships from the spiritual self to the family, local, religious, and national: the macrocosm. The weight, the pain, the immensity of it all. How could conversation, how could anything bring back those lost or take away the pain. This ugliness, meaningless, this boredom of repressive cycles. The thorns in the flesh. Perhaps, that ordinary, boring monotony of isolation, loss, and meaninglessness that T.S. Elliot immortalized in his poem, the Hollow Men is real:

his is the way the world ends

This is the way the world ends

This is the way the world ends

Not with a bang but a whimper.

But we have gathered here as followers of Christ, for us, it also unfolds within the Christian narrative. In fact, for the Israelites of the Hebrew bible, and really all religious folk, God is revealed in the vulnerable, in the absence, the silence. The Lord God says:, “Go out and stand on the mountain before the Lord, for theLord is about to pass by.” Now there was a great wind, so strong that it was splitting mountains and breaking rocks in pieces before the Lord, but the Lord was not in the wind; and after the wind an earthquake, but the Lord was not in the earthquake; 12 and after the earthquake a fire, but the Lord was not in the fire; and after the fire a sound of sheer silence.”

Maybe, as we spoke of the trauma and loss of 9 11, Shakespeare was right in calling tears holy water, maybe the silence and pain that resonated through the room was no longer isolated in the abyss of loneliness, but seeped, broke-through and made us more whole. After my partner and I were leaving church, we remarked how we appreciated feeling welcomed and listening to such intimate personal recollections and reflections. But we did not just listen, we also re-oriented ourselves to something beyond, we entrusted ourselves to that which we can not control. I felt lighter.

Yes, it was not solutions, but the most honest and helpless pleas that gripped us, that bound us in a holy sense of feeling. Perhaps, this is because vulnerability allows us to confront that which is repressed or rejected, consciously or unconsciously from the whole. And this whole begins from our own hearts to the borders built around nations. From the person we sit beside on the train to our support of tyrannical dictators in the middle East. We, we just visitors are a part of the ministry of presence. We showed up. We held-up and resonated with each other’s incredibly different struggles.

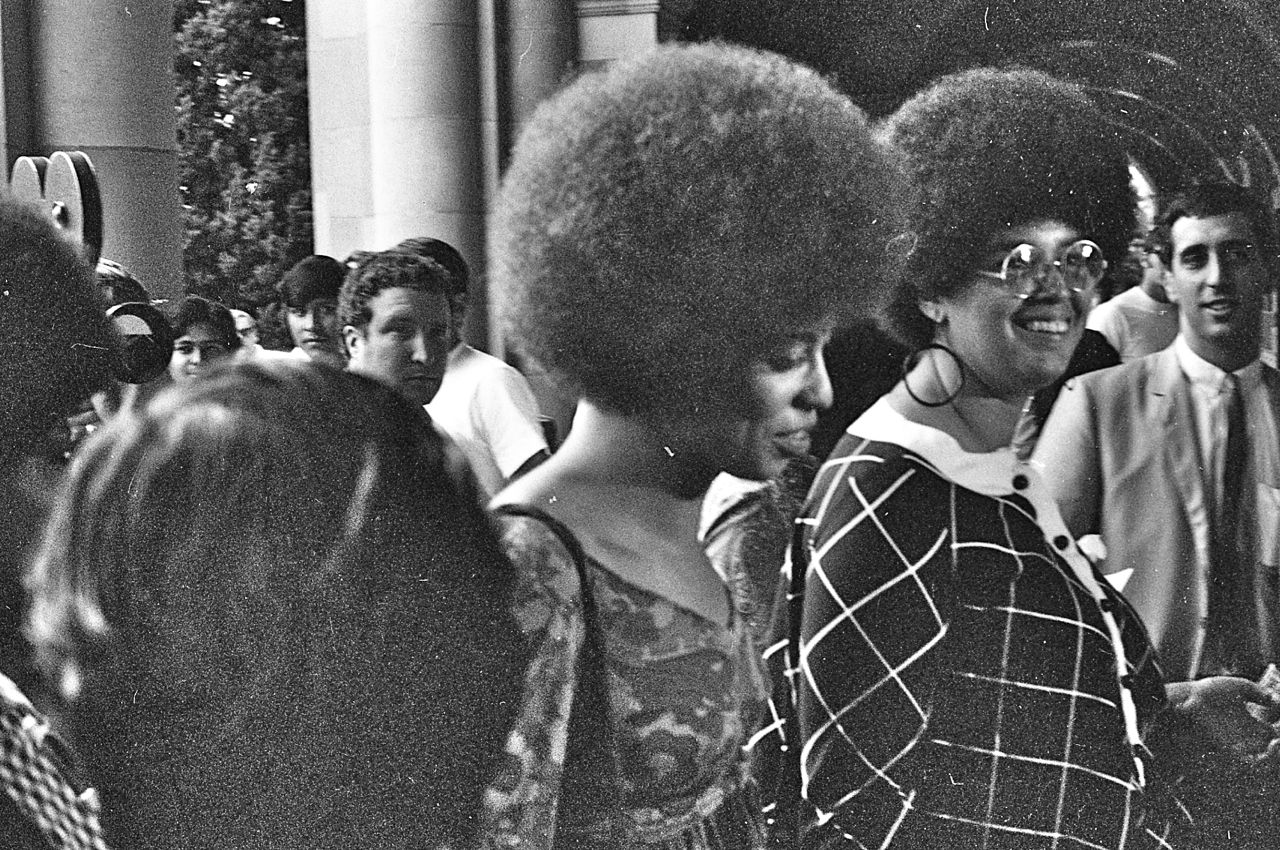

After returning from the Dominican Republic, I was reading Angela Davis’ book, Freedom. My thoughts were on Russia and the encroachment of freedom that returned. Speaking of her understanding of Black politics, in her book Freedom is a Constant Struggle, Ferguson, Palestine, And the Foundations Of Movement former black panther, academic, and activist, Angela Davis writes “the Black struggle in the US serves an emblem of the struggle for freedom. It’s emblematic of larger struggles for freedom.”

I came to realize that by claiming my personal vulnerabilities I was able to join the struggles of others and begin liberate myself from white supremacy. I started from my vulnerability: my immigrant, religious minority, short, poet, experience. It was not male whiteness I had to defend or white guilt to absolve. There is nothing to defend there: there is nothing good in domination. I do not think whiteness as the Western, objective, absolute truth is real. It is the impersonal cultural and economic systems that continue to leave people of color disproportionatly invisibilzed, brutalized or killed that are real. And for me, that means there is only privilege to be shared within these systems of resources. I do not not have to invest time defending whiteness which was only a supremacist construct hurting us both on a social plane. This is taking our weaknesses and vulnerabilities as our starting points, not notions of supremacy. That means that there is something spiritually expensive, holy about tears. They have moved people towards insight and action.

Upon my return, I began to see wholeness, the repression of church communities in Russia as the same repression of alternate economies when people of color are harassed and even murdered by US police for “violations” like selling CD’s (Alton Sterling), loose cigarettes (Eric Garner). The wholeness of the global justice struggle began to uncover. The Russian government’s attack on dissidents, LGBTQ, people of color, freethinkers, Muslims, and religious minorities is a crisis that to varying degrees joins the black struggle, the working class people’s struggle, the LGBTQ struggle, the feminist struggle across the world.

----

This fall will mark the first time I am not in school. Now I have loans. I am now in the world of adulthood. And I see how we become pulled apart by the gods of responsibility. Something has happened to the world of our daily life, especially in the screech and text vibration of the city. Job interviews and business pitches do not want vulnerability, but success, power.

Not only so, but constant attachment to solutions, the sound of verbal communication, to the certainty of light, digital connection, uncovers our deeper fear of silence, of darkness, of reality itself. It suggests that somehow, for us, words are superior to silence, light superior to darkness. And I think it is this kind of thinking, this orienation that allowed sexism, racism and neglect of nature and earth-spirituality. It suggests an inner and outer world where something is rejected and unaddressed, controlled or kept at arms length. But when we approach the birth of Christ, we read of John the Baptist, strengthening his spirit through discipline in the steep desert terraces and blunt escarpments of the Judean desert (Luke 1:80). There is seclusion, stillness, and silence. And ultimately, we read of Jesus, after his baptism in the Jordan River, compelled by the Holy Spirit to fast and be tested in that same strenuous terrain (Matthew 4:1).

How much energy, bodily and spiritual, is wasted on unresolved inner conflicts or what we call stress. I am afraid that unchecked, at their most tragic, these same energies can result in violence, whether individual, domestic or global. This energy could be channeled into finding our creaturehood through co-creation. We must begin to become whole and that takes just doing it, where even an instant counts:

confronting the challenge of confronting the real self, of resting in all our whole being, where prayer becomes resistance through self-surivival and expression. It takes reconnecting with all creation, especially what is most repressed, our bodies, sexuality, the earth, which feeds us. That is the place where vulnerability is home and renewed. We preserve our spirit from the thousands of needs that pull us apart. We may confront the thorn in the flesh; instead of being something we neglect and step on, hurting ourselves and then others, it teaches us. Then, right in our hand, the greatest thorn we hold in the greatest darkness, can become a match lighting the way to our calling: something powerful, a strength born within weakness.