Mountains fall before this grief,

A mighty river stops its flow,

But prison doors stay firmly bolted

Shutting off the convict burrows

And an anguish close to death.

Fresh winds softly blow for someone,

Gentle sunsets warm them through; we don't know this,

We are everywhere the same, listening

To the scrape and turn of hateful keys

And the heavy tread of marching soldiers. (Anna Akhmatova, "Requiem")

For the Russian-American poet, it is hard to imagine the poetical and political as neatly separable. If robust politics is vital for growth in society, then robust poetry understands the political dimensions of society. In some form, political realities emerged prominently in the work of Akhmatova, Mandelstam, Mayakovsky, Isaiah, Dante, Neruda, Baraka, Melville, Rich, Ginsberg, Sinclair. Most of these poets did not see themselves as political poets. As Neruda said, "… I am simply a writer. A free writer who loves freedom. I love the people. I belong to the people because I am one of them.” This politically-literate sensibility found expression in lines like "Stone of the sun, pure among territories, / Spain veined with bloods and metals, blue and victorious, / proletariat of petals and bullets, / alone alive, somnolent, resounding."

For these poets, poetry was not a political megaphone, but an aesthetic vision of truth, exposing, among other things, how the political operates. This does not mean it did not posses their sense of the political struggle and that evil is not made to appear ugly. For example, Akhmatova's poetry may have paradoxically been condemned as "apolitical" by Soviets for not formally supporting Soviet slogans, but landmark poems like "Requiem" unquestionably bore witness to the concrete terror of political persecution. They are some of the greatest achievements in poetry bearing witness to brutality. In fact, as Mandelstam's execution shows, it seems she avoided publishing the poem until 1953 for strategic reasons of safety. In the Euroasian continent, too often publish can mean perish.

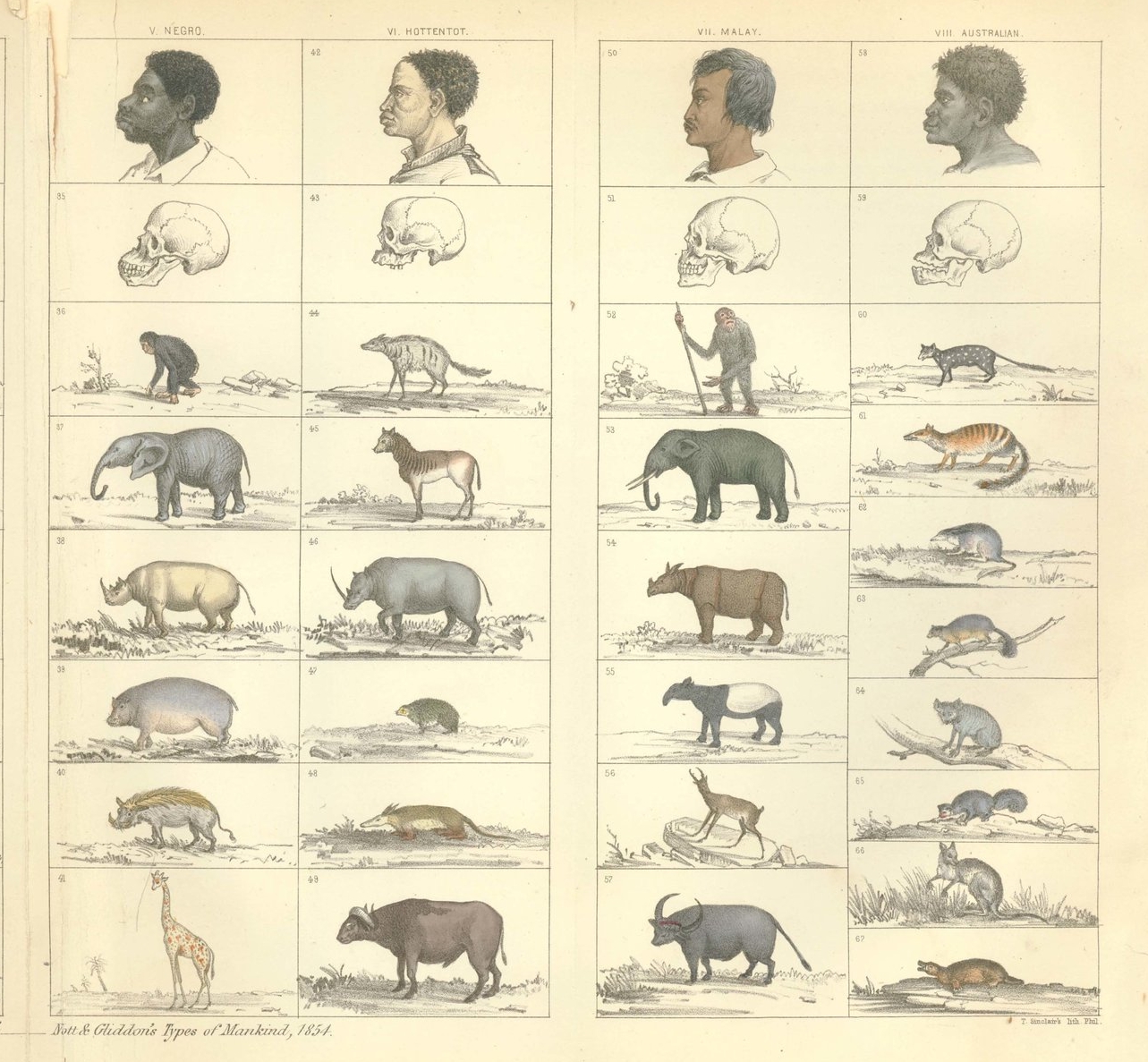

Before we move forward, I must offer a definition of what I mean by the political: the relationships between people and systems of power (whether governmental or more unofficial cultural power). This also means the abuse of power recognized by its systemic domination of a group or individual: authoritarianism, censorship, fascism, patriarchy, nationalism, classism, heterosexism, and racism. Poetry of witness testifies to an experience of political scope: the use or abuse of this power; it presents a vision expansive enough to show how something really works.

Throughout my undergraduate studies, I struggled to describe my approach to the political in poetry. The range of styles and perspectives is vast. It was Pound and Keats who came to the rescue. Their insight related to poetry and values, to a sense for right and wrong in the world. Pound's essays on an artist's responsibility to make "evil" appear "ugly" and "good" appear "beautiful" saved me in a very controversial way. It is still hard to understand how such a bright insight into the ethics of poetry was produced by a poet who once identified with Mussolini's fascism. Keats, on the other hand, helped me see musicality and imagination are not separable from truth and reality: truth is beauty, beauty is truth. One of the greatest expressions of this was in Oscar Wilde's Preface to The Picture of Dorian Grey:

Those who find ugly meanings in beautiful things are corrupt without being charming. This is a fault.

Those who find beautiful meanings in beautiful things are the cultivated. For these there is hope...

The nineteenth century dislike of Realism is the rage of Caliban seeing his own face in a glass.

The nineteenth century dislike of Romanticism is the rage of Caliban not seeing his own face in a glass.

However, throughout my undergraduate years and beyond, I understood that many poets are weary of didactic poetry, of poetry with political agenda. Many poets like W.H. Auden, Basil Bunting, and David Lehman have emphasized that poetry is not about political truth-telling, but a play of language, employing craft in service of the most advanced form of language. For this group, craft is central and the political interest is bias that dilutes an impersonal artistic world. Poetry understood in political terms, or political ideas emerging in a work, could be seen as didactic. The fact that art could risk being flattened by politics was something I agreed with, but I also thought art has important political implications. I was convinced there was a way to do it right. I was not alone. Some poets like Neruda, Rich, Baraka, Lorde offered a different view to the "apolitical poets." They suggested apolitical poetry, or poetry blind to political horror is privileged, revealing the poet's luxury of formal play for formal sake.

"I speak here of poetry as the revelation or distillation of experience, not the sterile word play that, too often, the white fathers distorted the word poetry to mean... For women, then, poetry is not a luxury." (Audre Lorde, "Poetry is Not a Luxury")

For poets like Lorde, poets must be responsible to both form and lived experience, craft and the world. Even if Brodsky resisted the political poet label, he was convinced ethics and aesthetics are connected, saying aesthetics is the mother of ethics because there are limits in the natural world. For example, the color wheel, one of the artist's central tools, has limits. The idea that poetry has a responsibility to the ways of the world, to truth, is currently understood as "poetry of witness." You can find "poetry of witness" in Carolyn Forche's anthology Against Forgetting as well as journals like Cortland Review, Witness, Muzzle, rock & sling, Matador Review, and Winter Tangerine. For poets of witness, technical maturity and ethical maturity, the political and personal, are not mutually exclusive. Here, Brodsky's poem "Bosnia Tune" finds consonance between form and the the suffering of the world, the aesthetic and truth:

As you pour yourself a scotch,

crush a roach, or check your watch,

as your hand adjusts your tie,

people die.

In the towns with funny names,

hit by bullets, cought in flames,

by and large not knowing why,

people die.

For years, I was convinced any resistance to the political in poetry (including concerns about the flatness of political language) was suspect, status-quo and dangerous. Looking back, my view has changed, but only to a certain extent. What remains: the inseparability of politics and poetry. The best of our spiritual traditions and the latest scientific evidence suggest the inherent interdependence of all of life. If this is the case, it is impossible, and I would argue, dangerous to stand outside political engagement. And I would argue this is because my Russian immigrant status made me aware of something important. Whether through family history or bullying in high school for my immigrant name, I know what it means to be deemed separate, outsider, and abused for things outside my control. But at the same time, my honesty forces me to admit that I enjoy privilege as a white male. In other words, through these experiences, I began to uncover my complex sense of place in the relations of the world.

Nevertheless, I see I was missing two important things:

Letting conventional politics (and political language) drive the work of art can lead to impoverished poetry, lacking perceptiveness and imagination. Reality includes the political, but reality surpasses the political: here, our immediate relationship to a situation, a time and place, comes first. Forche understands it this way: "The poetry of witness reclaims the social from the political and in so doing defends the individual against illegitimate forms of coercion." If one is an open, honest, responsible poet, and if the artistic process is trusted, good "poetry of witness" emerges organically from the breadth and depth of the artistic vision.

In other words, the open, responsible artist listens deeply, explores and understands his/her relationship to the world and the range of emotional textures. The inclusiveness of the artist will be curious about the experiences of others while being honest to their limited vantage point. Through the skillful use of craft, the poet may uncover insight into the interrelations of power and abuse of power. At its best, what is left is a poem that offers a direct, sensory experience, revealing the tensions of power as well as our potential to transform the ugly abuse of power into the beautiful use of power. The work is best when the form allows the experience to speaks for itself, when the craft most precisely serves the whole experience.

The poet who does not see their art as a part of the struggles of larger society may risk irresponsibility, abandoning their duty to bear witness to truth. While I agree that political language can be impoverished, I do not see innovative language itself (without any connection to the larger witness to truth) as the fullest expression of poetry. If the artist is blind to the struggles of his/her neighbor, his/her vision risks being narrow and sometimes even lopsided; the art may be technically successful, but it may distort the truth of how their artistic vision is inescapably connected to power, privilege and the abuse of power.

Nevertheless, the problem of bearing witness to experiences that are not yours can be problematic. The poet Claudia Rankine has emerged with the most substantive response. For Rankine, the response should not be cautious avoidance, but a radical honesty of one's social location and how power is functioning through it. As Claudia Rankine writes in Whiteness and Racial Imaginary: "This is not to say that the only solution would be to extend the imagination into other identities, that the white writer to be antiracist must write from the point of view of characters of color. It’s to say that a white writer’s work could also think about, expose, that racial dynamic...Perhaps the way to expand those limits is not to “enter” a racial other but instead to inhabit, as intensely as possible, the moment in which the imagination’s sympathy encounters its limit."

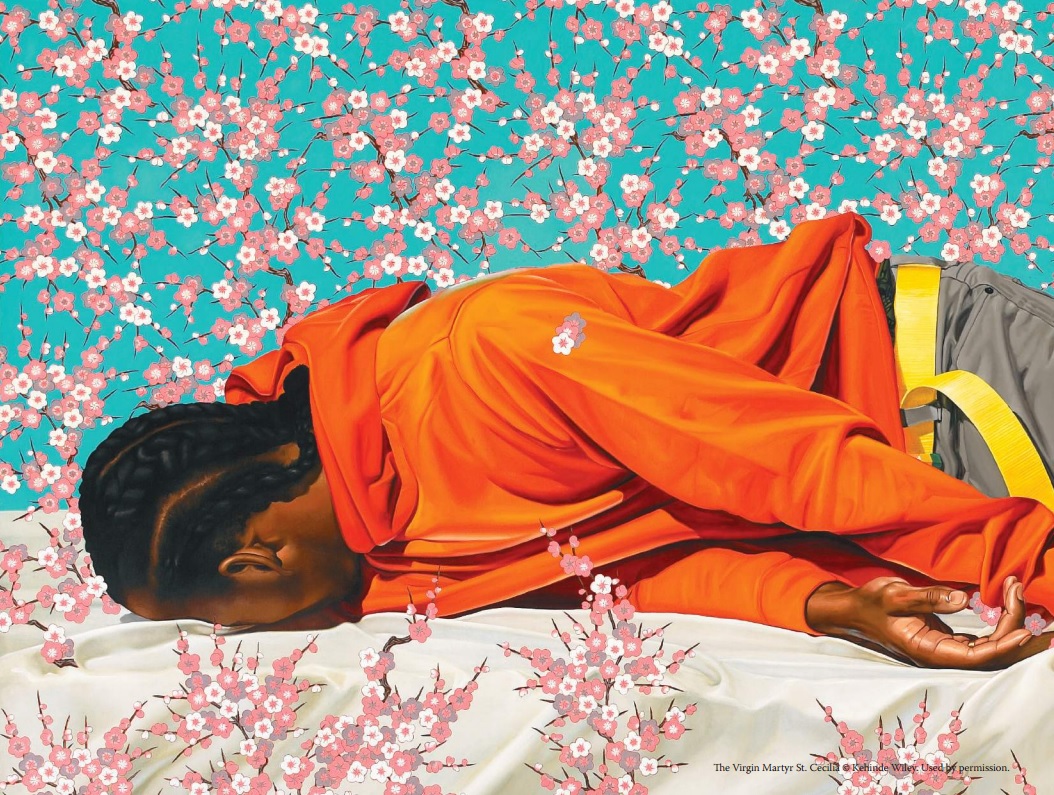

This is the intuition I always had as a poet, but struggled and still struggle to express best. For me, good poetry has always offered, not just good form, but flashes of truth, the fullness of a human situation, uncovered through the formal effects of language. Like Kendrick's lyrics or "decolonize this place" stickers, it has role as an activist tool as much as a cellphone revealing police brutality. But it works through a three part process: 1) the materials are words, words with a range of sensory and intellectual properties: images, sounds, ideas, colors, movements, concepts, textures, smells, tastes etc., 2) the form is the shape the materials take, how the words are arranged to produce the intended experiance, 3) the artistic vision is the emotional insight into human experience, it either succeeds or fails to honor the complexity of the world. The poet's openness is central: it is a demonstration of their ethical maturity to accept uncomfortable information and bring it to its corresponding aesthetic form.

Of course poems are not absolute. The poem is not The Fullness of truth, but it is a fullness: a dimension, a window into part of the Fullness of truth. If the poet is open, honest and responsible, the completed poem is a gift to the broader world; it has political implications, and by being a compelling bodily experience, it has implications in all spheres of life. The poem becomes part of the reader's body and it is carried into the world. If others resonate with the work, it becomes a shared reality and new feature in the fabric of culture. As Rich wrote, "poetry isn't revolution, but a way of knowing why it must come."

A SHORT SPEECH FOR MY FRIENDS

Amiri Baraka

A political art, let it be

tenderness, low strings the fingers

touch, or the width of autumn

climbing wider avenues, among the virtue

and dignity of knowing what city

you’re in, who to talk to, what clothes

—even what buttons—to wear. I address

/ the society

the image, of

common utopia.

/ The perversity

of separation, isolation,

after so many years of trying to enter their kingdoms,

now they suffer in tears, these others, saxophones whining

through the wooden doors of their less than gracious homes.

The poor have become our creators. The black. The thoroughly

ignorant.

Let the combination of morality

and inhumanity

begin.